Over the past three decades, instructional models such as the flipped classroom, inverted classroom, flipped learning, or inverted learning have gained considerable traction, drawing the interest of both educational practitioners and researchers (Lee, 2023). Although these terms share similar definitions, they have gradually given way to the term ‘flipped learning’, hereafter abbreviated as FL in this paper. In 2012, FL emerged as an experimental learning approach in a high school in the United States (Bergmann & Sams, 2012). Presently, FL enjoys widespread recognition across diverse educational settings (Lee & Choi, 2019). This paper aims to explore the historical path of FL, the underlying theories guiding its implementation, and an examination of its potential benefits and challenges. We will argue that FL, by utilising modern technology and innovative teaching strategies can significantly enhance student engagement and academic outcomes while introducing substantial challenges that educators must address. Lastly, we will explore the future prospects for FL, considering various opportunities and threats posed by advancements in artificial intelligence technologies and their potential impact on FL within the classroom.

Figure 1. A History of Flipped Learning. Video created with Doodly (2024), Elevenlabs (2024) and Ableton (2024).

The complex evolution of FL has given rise to multiple definitions. Perspectives range from the utilisation of traditional methods of in-class knowledge transmission to more contemporary forms of blended learning. Bergmann & Sams (2012) originally proposed a more traditional approach to FL, defining it as a model where classwork is conducted at home, and homework is completed in-class. Other definitions have incorporated the inclusion of group and collaborative work within the classroom (Bishop & Verleger, 2013; Lo & Hew, 2017; Brewer & Movahedazarhouligh, 2018; Bond, 2020). However, as blended learning offers a blend of synchronous face-to-face learning and asynchronous online experiences (Garrison & Kanuka, 2004; Garrison & Vaughan, 2008), FL may also involve content learning online before class, followed by active learning during face-to-face classroom activities (Chen et al., 2018). The traditional FL definition (Bergmann & Sams, 2012) also allows for the use of various media types, including video (Lee et al., 2016; Lo & Hew, 2017), reading assignments and PowerPoint presentations (Lai & Hwang, 2016; Giannakos et al., 2018; Lee & Choi, 2019). These pre-class activities can be delivered through diverse online platforms such as learning management systems, Microsoft Teams and YouTube (Caligaris et al, 2016; Wang, 2017; Yilmaz, 2017). In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, newer FL approaches have emerged including bichronous and hyflex learning, which use different combinations of synchronous and asynchronous activities (Parra & Abdelmalak, 2016, Viriya, 2022). Synthesising these perspectives, we will therefore define FL as a teaching strategy that uses various forms of media or solutions to facilitate pre-class online knowledge acquisition and in-class collaborative knowledge application.

Figure 2. Introduction to Flipped Learning (Bergmann, 2023).

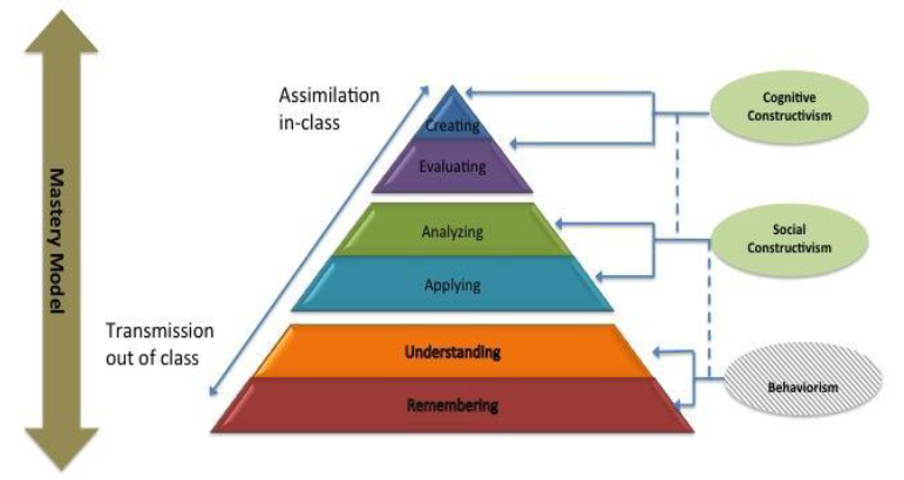

Bergmann & Sams (2012) and Eppard & Rochdi (2017) have discussed how FL is based on Bloom’s mastery theory, allowing students to learn at their own pace. Each discrete knowledge objective should be mastered to enable the success of subsequent sections. Bergmann & Sams (2012) also explained that technology has now enabled the mastery theory, where historically (in the 70s and 80s) the practicalities of independent or group learning were difficult to manage.

Talbert (2012) and Eppard & Rochdi (2017) described the transmission and assimilation of learning as an important part of FL. The transmission of information is acquired independently out of class, while assimilation occurs during class, which requires greater critical reasoning. Eppard & Rochdi (2017) associated the transmission of information with behaviourism. Ertmer & Newby (2013) explained that behaviourism focuses on the consequences of learning performances and responses to enable the repetition of behaviour. This method facilitates learning that involves recalling facts, generalisations, applying explanations, and performing specified procedures automatically.

The success of FL is further supported by constructivist learning theories, particularly Piaget’s (1964) cognitive constructivism and Vygotsky’s (1978) social constructivism. Ertmer & Newby (2013) described constructivism as a theory that enables learning by creating meaning from experience. Constructivist teachers use instructional methods and strategies to help learners explore and think more deeply about subjects. Vygotsky’s (1978) social constructivism suggests that learners construct knowledge through social interaction, interpretation, and understanding. This theory emphasises that knowledge creation is inherently linked to the social context in which it occurs, framing learning as an active process of knowledge construction.

Vygotsky considered learning a process where students are assisted by more competent individuals, optimising learning through collaboration within the learner’s zone of proximal development. He defines this zone as the difference between the actual developmental level achieved by independent problem-solving and the potential level achieved through guidance or collaboration. Within the FL model, teachers create opportunities for problem-solving, peer learning, and active learning (Abeysekera & Dawson, 2015), thus enabling access to social constructivism. Adams (2006) points out that constructivism focuses on learning rather than performance, encouraging learners to be co-constructors of meaning and knowledge.

Piaget’s (1964) cognitive constructivism theory aligns with Vygotsky’s, maintaining that higher levels of learning require peer interaction. The theory of cognitive development underpins new knowledge acquisition through experiences, enabling learners to create mental models that can be refined and made more sophisticated through assimilation (Eppard & Rochdi, 2017). Piaget (1964) emphasised the active role of learners in constructing their understanding of concepts through firsthand experiences and interactions with their environment. In FL, students engage with pre-class materials independently, constructing knowledge before participating in collaborative activities during face-to-face or synchronous sessions. The self-directed nature of FL encourages students to explore, reflect, and make meaning of content at their own pace, aligning with Piaget’s (1964) emphasis on active learning and cognitive development. By grappling with concepts independently before engaging in discussions and problem-solving activities, students are more likely to internalise knowledge and develop a deeper understanding, consistent with Piaget’s principles of assimilation and accommodation.

Eppard & Rochdi (2017) proposed that FL methodology is successful due to the juxtaposition and dynamic interaction of these different learning theories and models. Figure 3 (below), adapted from Eppard & Rochdi (2017), visualises this interaction based on Anderson et al.'s (2001) updated model of Bloom's Taxonomy. The diagram illustrates the overlap between learning theories as part of the FL process. The theory of behaviourism links with the transmission of information and the remembering and understanding foundation of knowledge. This foundation enables learners to work with peers to analyse and apply their knowledge in a social constructivist way, assimilating knowledge. Finally, these interactions make possible the creative and evaluating sections of Bloom’s Mastery Theory using cognitive constructivism.

Figure 3. Visualisation of Learning Theories. Adapted from Eppard and Rochdi (2017).

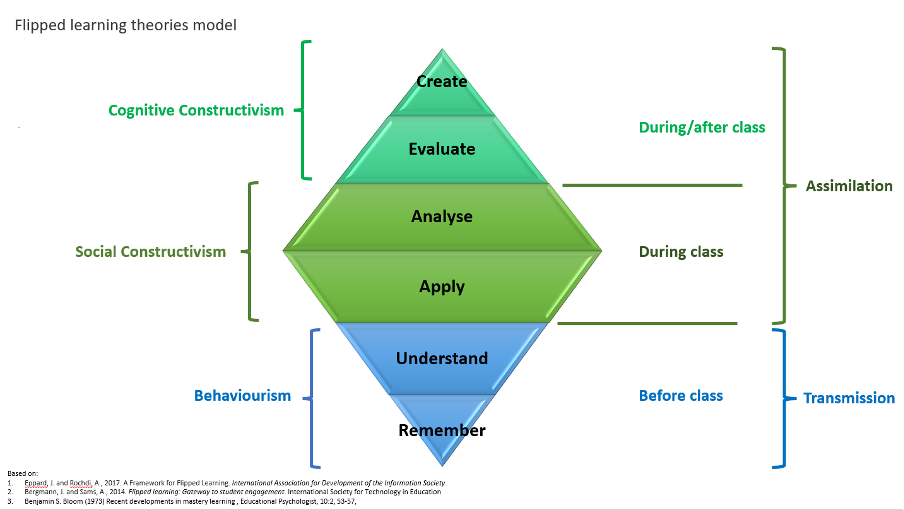

Figure 3 shows that the majority of most time and effort is directed towards the initial behaviourist sections of remembering and understanding. A different model can be presented (Figure 4) if used with Bergmann & Sams' (2014) version of Bloom's Taxonomy and FL. This reveals how the different theories combine and influence each other. In this model, the primary focus is on the analysis and application of knowledge within the classroom, aligning with the principles of social constructivism. Conversely, the behaviourist components of knowledge acquisition and information transmission are afforded less emphasis.

Figure 4. Learning Theories adaptation from Eppard & Rochdi (2017) combined with Bergmann & Sams (2014) version of Bloom's Taxonomy.

Since 2012, numerous studies have proclaimed the potential benefits of FL (Bergman & Sams, 2012; Enfield, 2013; Farah, 2014; Eppard & Rochdi, 2017). Akcayir & Akçayır (2018) underscored the efficient utilisation of in-class time, which facilitates more learner-centred activities such as group discussions, interactive activities, and feedback. Learners often construct knowledge both inside and outside the classroom through activities and assignments that promote critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Brewer & Movahedazarhouligh, 2018). As such, Rahmen et al. (2020) suggested that a paradigm shift in learning and teaching styles is needed. However, Eppard & Rochdi (2017) stressed that not all areas of success with FL are yet understood. Obstacles such as learners' unfamiliarity and reluctance towards FL can impede its implementation, potentially causing anxiety and resistance to change (Akcayir & Akçayır, 2018; Brewer & Movahedazarhouligh, 2018). Additionally, educators may resist the paradigm shift from being a 'sage on the stage' to a 'guide on the side' (Baker, 2000).

Nevertheless, much of the research concerning the effectiveness of FL indicates improved academic and learning outcomes, predominantly assessed through course grades or test scores (Love et al., 2013; Mattis, 2014; Sowa & Thorson, 2015). For instance, Day (2018) conducted a comparative study in Boston, examining two groups of students: one employing traditional teaching methods and the other adopting a flipped classroom. The results demonstrated significant disparities, with the flipped classroom group attaining higher grades than their peers in the traditional setting. Similarly, by using a combination of pre-recorded lectures, online quizzes and in-class group activities, Awidi & Paynter (2019) affirmed that the FL model had shown transformative potential in boosting student engagement and enhancing learning outcomes. However, a three-year study comparing the traditional model to a flipped format, found that higher learning outcomes require more effort and attention to detail than the traditional teaching format (Taha et al., 2016).

Another outcome frequently explored in FL research is student engagement or motivation. It has been reported that students experience high levels of motivation and engagement in their learning (Awidi & Paynter, 2019; Gündüz & Akkoyunlu, 2019; Jian, 2019). A review by Akcayir & Akçayır (2018) highlighted that the flipped approach boosted student motivation by up to 18% and active engagement by up to 14%. Schmidt & Ralph (2016) also found that FL increased student engagement by 80%. However, some findings reveal challenges with student motivation and self-regulation, particularly during pre-class learning. Heitz et al. (2015) reported that a significant number of students often fail to complete assigned pre-class tasks. Given that these activities are integral to FL, their completion directly affects FL's effectiveness. Lee (2023) suggested that distractions during online content viewing, feelings of helplessness when facing difficulties, or the need for clarification can lead to disengagement. Therefore, it is crucial for educators to reinforce the importance of pre-class learning as a foundational element of FL. Furthermore, Yilmaz (2017) noted a decrease in motivation with FL, attributing this to students' technological capabilities to access the pre-classroom content. To enhance student self-regulation, strategies such as reviewing students’ written notes, administering online quizzes, or providing structured study schedules could be effective (Cheng et al., 2019). Additionally, Sergis et al. (2018) advocated for the use of self-determination theory, a psychological framework for understanding motivation developed by Ryan & Deci (2000). By meeting the three basic needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, this can significantly improve cognitive learning outcomes and increase student satisfaction with the FL process.

As Bergmann & Sams (2012) observed, the cornerstone of an effective flipped classroom is technology. The use of technology in FL provides an opportunity to integrate digital tools into the classroom and mediate non-digital processes and practices (Eppard & Rochdi, 2017). The benefits include capabilities to skip forward, pause, and rewind videos (Lipomi, 2020), and to repeat or learn additional content at the student's own pace (Brewer & Movahedazarhouligh, 2018; Birgili et al., 2021), thus offering a more flexible approach to individual learning. According to Selwyn (2016), digital technology can empower educational change and enable the transformation of educational practices.

However, students and educators often confront technical challenges related to infrastructure, access to devices, and proficiency in technology skills (Lee, 2023). Access to online pre-recorded videos and content can pose significant hurdles for students lacking electronic devices (Gilboy et al., 2015). Furthermore, some may face difficulties due to insufficient experience in navigating technology and online learning systems. This could promote inequalities, hinder students' progress and increase the digital divide (Selwyn, 2016). For FL to be effective for all learners, issues related to the digital divide need to be addressed. Selwyn (2016) summed this up: "In striving to make the best use of technology in education, surely we need to ensure that all forms of digital education are pursued primarily in the general interests of the public rather than the narrow interests of the well-resourced and privileged few?" (pp. 159).

Similarly, teachers may have to deal with internet connectivity issues and struggle to upload video lectures (Gilboy et al., 2015). Additionally, these videos may be of poor-quality owing to inadequate ICT skills (Lo & Hew, 2017). For successful online content delivery, teachers require the appropriate technological tools to record, edit, and publish video lectures, a process that demands meticulous planning, time, and effort (Asad et al., 2022). As such, Bergman (2014) identified technology as a significant challenge in adopting the flipped classroom model, underscoring the necessity to carefully align the choice and application of technological tools with the specific classroom context. Conole (2015) proposed the 7Cs Learning Design Framework, designed to aid educators in making pedagogically sound decisions that appropriately utilise digital technologies (figure 5).

Figure 5 – The 7Cs Learning Design Framework (Conole, 2015). Created with Adobe After Effects (2024), Elevenlabs (2024), Ableton (2024) and Camtasia (2024).

Conole (2015) noted that educators often struggle with effective planning due to insufficient digital literacy, lack of support, and limited time to experiment with technologies. In this case, lecture materials could incorporate Open Educational Resources (OER) such as variety of existing video learning content from MOOCs or platforms like TED (2024) (figure 6). These resources, alongside the use of the 7C’s Learning Framework, can provide vital support for addressing significant technological challenges that educators encounter in designing and implementing the FL model.

The use of technology in education has also introduced terms such as blended, bichronous and hyflex learning. A search on Google Scholar for FL in conjunction with blended learning provides almost 98,000 results, indicating significant interest and a link between FL and blended learning.

Figure 7. Blended, Bichronous and Hyflex Learning in a Flipped Learning Context. Presented by Samantha Watson (2024). Created with Ableton (2024) and Camtasia (2024).

The emergence of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI), capable of generating new content from training data, has sparked significant debate regarding its potential impact on future FL practices (Gilson et al., 2023; Su & Yang, 2023; Tlili et al., 2023; Farrokhnia et al., 2024). These models are engineered using a blend of deep learning techniques and extensive pretraining on large datasets, which equips them to decipher language patterns and relationships. This ability enables them to produce contextually relevant responses (Lo, 2023). A prominent example is Chat GTP, a GAI chatbot which can assist, mentor, or support students in learning course materials (Wollny et al., 2021). While some studies praise chatbots as effective tools for facilitating adaptive learning and access to information (Gilson et al., 2023; Su & Yang, 2023), other research underscores the potential risks these technologies pose to educational practices (Tlili et al., 2023; Farrokhnia et al., 2024).

Diwanji et al. (2018) proposed that chatbots can uphold the fundamental principles of the FL classroom, such as self-directed learning and learner-centered instruction. Furthermore, Han et al. (2022) suggested that chatbots can be programmed to facilitate self-directed learning and provide study tips, enhancing student autonomy and creating a sense of ownership over their learning journey. Huang et al. (2019) and Chen et al. (2020) noted that immediate feedback, aligned with specific learning objectives, can contribute to improved student performance and learning outcomes. This feedback allows educators to tailor instruction to meet individual learning needs. Additionally, Winkler & Söllner (2018) observed that chatbots have the potential to create learning materials customised to the specific needs of students, further facilitating personalised learning experiences and thereby increasing engagement and motivation.

However, the integration of chatbots within the FL framework remains under-researched, prompting Bahja et al. (2020) to underscore ethical and privacy concerns as a significant challenge for educators. Institutions should be tasked with ensuring the non-retention of personal data, maintaining student privacy, and securing data storage (Hasal et al., 2021). Compliance with data protection regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union (Regulation GDPR, 2018), is crucial. Additionally, Valério et al. (2020) suggested that chatbots should provide opt-in or opt-out features to protect students who prefer not to participate. Another major issue is the reliability and validity of the information chatbots provide, which depends on the quality of the data they are programmed with, potentially leading to inaccurate or inappropriate feedback (Chuah & Kabilan, 2021; Vanichvasin, 2021). Consequently, future research should focus on methods to enhance the reliability and validity of chatbot feedback, while also addressing potential biases (Kim et al., 2021). Moreover, educators should consider the level of human interaction available to students and create opportunities for meaningful and personalised engagement (Furrer et al., 2014).

As discussed previously, a key outcome frequently explored in FL research is student engagement or motivation, particularly in pre-class learning. Maslow (1981) highlighted that motivation is a critical factor in successful learning. However, the present FL approach often employs learning motivation theory based on reward and punishment mechanisms, termed extrinsic motivation. Rob (2014) noted that this type of motivation leads many students to engage with course materials primarily for the reward of grades. Conversely, Tileston (2010) argued that students perform better when they are intrinsically motivated, where motivation stems first from an interest in the activity itself, enhancing the learning experience (Huang et al., 2023). Recent methods that foster intrinsic motivation include game-based learning (Hwang et al., 2013; Molins-Ruano et al., 2014) and mobile learning (Huang et al., 2016).

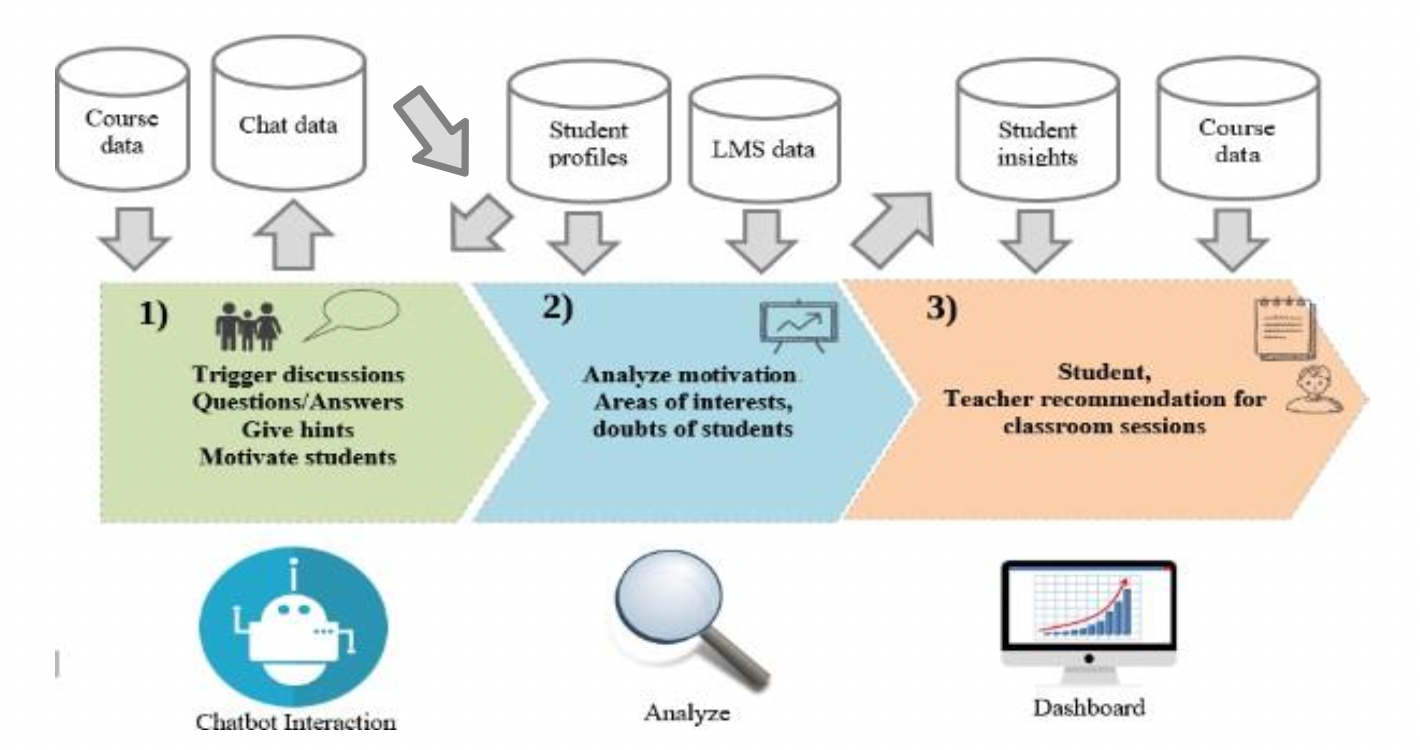

Building on Klemm’s (2002) work on conversational theory, Diwanji et al. (2018) posited that GAI could significantly increase intrinsic motivation in FL through written dialogues between teachers and students. Utilising a design science methodology, they developed a chatbot integrated with a dashboard for students and a recommendation system for teachers to facilitate students’ preparation for FL. This chatbot not only initiates but also engages in conversations relevant to course content, thereby enhancing classroom discussions. It is programmable to utilise specific topics and can dynamically form student groups for discussions based on their backgrounds, interests, and motivation levels, creating engaging and diverse interactions (figure 8).

Figure 8: Concept of chatbot supported application for the flipped classroom (Diwanji et al., 2018).

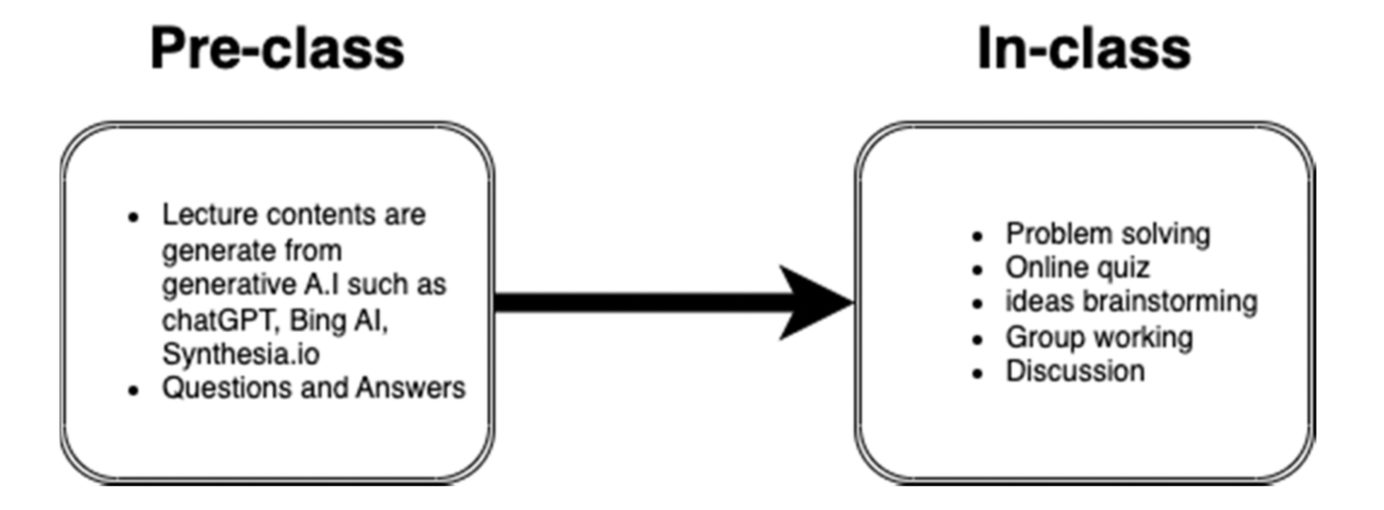

To further mitigate the potential negative impacts of GAI on educational practices, Abdulmalik et al. (2023) proposed a modified flipped learning model (MFL) designed to enhance student learning outcomes and equip them with essential skills such as critical thinking, creativity, and adaptability (figure 9). This model integrates elements of FL but includes tailored modifications to incorporate GAI technology effectively. It shifts the traditional role of the teacher to facilitate student ownership of learning, with students using GAI for pre-class activities and content creation. Under the guidance of their teachers, students refine this content in class, thus becoming co-creators of knowledge and creating a deeper sense of ownership and creativity. The model also encourages collaboration and peer-to-peer learning as students share and discuss their AI-generated content during class sessions, enhancing their understanding of the subject matter. Addressing biases, and ensuring accuracy and reliability are central concerns of the MFL model, which advocates for responsible and ethical usage of GAI in and out of the classroom.

Figure 9. The Modified Flipped Learning Model (MFL) (Abdulmalik et al., 2023).

Figure 10. Flipped Learning Policy Considerations. Presented by Samantha Watson (2024). Created with Adobe After Effects (2024), Ableton (2024) and Camtasia (2024).

In conclusion, FL has demonstrated significant potential in transforming traditional educational practices by nurturing deeper student engagement, enhancing critical thinking skills, and improving academic outcomes. The theoretical foundations of FL, rooted in Bloom's mastery theory and constructivist learning theories, support its effectiveness in promoting student-centered learning. However, the implementation of FL is not without its challenges. Technological barriers, such as access to devices and digital literacy, can impede its adoption. Additionally, students' unfamiliarity with the FL model and the increased responsibility for pre-class preparation can affect motivation and engagement. Despite these challenges, numerous studies have shown that FL can lead to higher academic performance and greater student satisfaction when effectively implemented.

The integration of generative AI into FL presents new opportunities to further personalise learning and provide real-time feedback, potentially enhancing student motivation and learning outcomes. However, it also raises concerns about data privacy, academic integrity, and the digital divide. Addressing these issues requires careful planning and the development of clear policies to ensure ethical and effective use of AI in education.

Overall, while flipped learning offers promising benefits, its success depends on overcoming the associated challenges and leveraging technological advancements responsibly. By focusing on student engagement, motivation, and the thoughtful integration of AI, educators can harness the full potential of FL to create more dynamic, interactive, and effective learning environments.

Abdulmalik, A., Basheer, M., Ahmad, Yarima, K.I., Zakari, A., II, A., Hussaini, A., Kademi, H., Danlami, A., Sani, M., Bala, A. and Lawan, S. 2023. Modified Flipped Learning as an Approach to Mitigate the Adverse Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Education. Education Journal.

Abeysekera, L. and Dawson, P. 2015. Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: definition, rationale and a call for research. Higher Education Research & Development. 34, pp.1–14.

Ableton 2024. Creative tools for music makers | Ableton. [Accessed 19 May 2024]. Available from: https://www.ableton.com/en/.

Adams, P. 2006. Exploring social constructivism: theories and practicalities. Education 3-13. 34(), pp.243–257.

Adobe After Effects 2024. Motion graphics software | Adobe After Effects. [Accessed 19 May 2024]. Available from: https://www.adobe.com/uk/products/aftereffects.html.

Ahmadi, D. and Reza, M. 2018. The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review. International Journal of Research in English Education. 3(2), pp.115–125.

Akcayir, G. and Akçayır, M. 2018. The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education. 126.

Anderson, L., Krathwohl, D., Airasian, P., Cruikshank, K., Mayer, R., Pintrich, P., Raths, J. and Wittrock, M. 2001. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives.

Asad, M., Ali, R., Churi, P. and Moreno Guerrero, A. 2022. Impact of Flipped Classroom Approach on Students’ Learning in Post-Pandemic: A Survey Research on Public Sector Schools. Education Research International. 2022, pp.1–12.

Awidi, I.T. and Paynter, M. 2019. The impact of a flipped classroom approach on student learning experience. Computers & Education. 128, pp.269–283.

Bahja, M., Hammad, R. and Butt, G. 2020. A User-Centric Framework for Educational Chatbots Design and Development In:, pp.32–43.

Baker, J.W. 2000. The ‘Classroom Flip’: Using Web Course Management Tools to Become the Guide by the Side. Selected Papers from the 11th International Conference on College Teaching and Learning., pp.9–17.

Barnard-Brak, L., Lan, W., To, Y., Paton, V. and Lai, S.-L. 2009. Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education. 12, pp.1–6.

Bergmann 2014. The Second Hurdle to Flipping Your Class – EdTechReview. [Accessed 19 May 2024]. Available from: https://www.edtechreview.in/trends-insights/insights/the-second-hurdle-to-flipping-your-class/.

Bergmann, J. and Sams, A. 2012. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. Eugene, Or: International Society for Technology in Education.

Bergmann, J. and Sams, A. 2014. Flipping for Mastery. Educational Leadership. 71(4), pp.24–29.

Bernacki, M., Vosicka, L., Utz, J. and Warren, C. 2020. Effects of Digital Learning Skill Training on the Academic Performance of Undergraduates in Science and Mathematics. Journal of Educational Psychology. 113.

Birgili, B., Seggie, F.N. and oğuz, E. 2021. The trends and outcomes of flipped learning research between 2012 and 2018: A descriptive content analysis. Journal of Computers in Education. 8.

Bishop, J.L. and Verleger, M. 2013. The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings.

Bond, M. 2020. Facilitating student engagement through the flipped learning approach in K-12: A systematic review - Data Extraction Coding Tool.

Brewer, R. and Movahedazarhouligh, S. 2018. Successful stories and conflicts: A literature review on the effectiveness of flipped learning in higher education. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 34.

Bullmaster-Day, M.L. 2011. Online and Blended Learning: What the Research Says. New York, NY: Kaplan K12 Learning Services.

Caligaris, M., Rodríguez, G. and Laugero, L. 2016. A First Experience of Flipped Classroom in Numerical Analysis. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 217, pp.838–845.

Chan, C. 2023. A comprehensive AI policy education framework for university teaching and learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 20.

Chen, K.S., Monrouxe, L., Lu, Y., Jenq, C.-C., Chang, Y., Chang, Y.-C. and Chai, P.Y.-C. 2018. Academic outcomes of flipped classroom learning: a meta‐analysis. Medical Education. 52.

Chen, L., Chen, P. and Lin, Z. 2020. Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review. IEEE Access. 8, pp.75264–75278.

Chuah, K.-M. and Kabilan, M.K. 2021. Teachers’ Views on The Use of Chatbots to Support English Language Teaching in a Mobile Environment. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET). 16(20), p.223.

Coates, H. 2010. Getting first-year students engaged. Australasian Survey of Student Engagement (AUSSE).

Conole, G. 2015. The 7Cs of learning design: a new approach to rethinking design practice In: S. Bayne, C. Jones, M. de Laat, T. Ryberg and C. Sinclair, eds. Lancaster University: Networked Learning Conference, pp.502–509.

Crouch, C.H. and Mazur, E. 2001. Peer Instruction: Ten years of experience and results. American Journal of Physics. 69(9), pp.970–977.

Day, L.J. 2018. A gross anatomy flipped classroom effects performance, retention, and higher-level thinking in lower performing students. Anatomical Sciences Education. 11(6), pp.565–574.

Diwanji, P., Hinkelmann, K. and Witschel, H.F. 2018. Enhance Classroom Preparation for Flipped Classroom using AI and Analytics In:, pp.477–483.

Doodly 2024. Doodly | Voomly Cloud. [Accessed 19 May 2024]. Available from: https://www.doodly.com/.

Elevenlabs 2024. AI Voice Generator & Text to Speech. ElevenLabs. [Online]. [Accessed 19 May 2024]. Available from: https://elevenlabs.io.

Elliott, R. 2014. Do students like the flipped classroom? An investigation of student reaction to a flipped undergraduate IT course In:, pp.1–7.

Enfield, J. 2013. Looking at the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Model of Instruction on Undergraduate Multimedia Students at CSUN. TechTrends. 57(6), pp.14–27.

Eppard, J. and Rochdi, A. 2017. A Framework for Flipped Learning. International Association for the Development of the Information Society.

Ertmer, P. and Newby, T. 2008. Behaviorism, Cognitivism, Constructivism: Comparing Critical Features From an Instructional Design Perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly. 6, pp.50–72.

Farah, M. 2014. The Impact of Using Flipped Classroom Instruction on the Writing Performance of Twelfth Grade Female Emirati Students in the Applied Technology High School (ATHS). Dubai: The British University in Dubai.

Farrokhnia, M., Banihashem, S.K., Noroozi, O. and Wals, A. 2024. A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: Implications for educational practice and research. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. 61(3), pp.460–474.

Flipped Learning Global Standards Summit 2018. Flipped Learning Global Standards Summit. Academy of Active Learning Arts and Sciences. [Online]. [Accessed 19 May 2024]. Available from: https://aalasinternational.org/flipped-learning-global-standards-summit/.

Flipped Learning Network 2024. Home_Page. Flipped Learning Network Hub. [Online]. [Accessed 4 May 2024]. Available from: https://flippedlearning.org/.

Fullan, M., Azorín, C., Harris, A. and Jones, M. 2023. Artificial intelligence and school leadership: challenges, opportunities and implications. School Leadership and Management., pp.1–8.

Furrer, C., Skinner, E. and Pitzer, J. 2014. The Influence of Teacher and Peer Relationships on Students’ Classroom Engagement and Everyday Resilience In: D. Shernoff and J. Bempechat, eds. NSSE YearbookEdition: Engaging Youth in Schools: Evidence-Based Models to Guide Future Innovations. Teachers College Record.

Garrison, D. and Kanuka, H. 2004. Blended Learning: Uncovering Its Transformative Potential in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education. 7, pp.95–105.

Garrison, D.R. and Vaughan, N.D. 2008. Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and Guidelines. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Giannakos, M.N., Krogstie, J. and Sampson, D. 2018. Putting Flipped Classroom into Practice: A Comprehensive Review of Empirical Research In: D. Sampson, D. Ifenthaler, J. M. Spector and P. Isaías, eds. Digital Technologies: Sustainable Innovations for Improving Teaching and Learning. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp.27–44.

Gilboy, M.B., Heinerichs, S. and Pazzaglia, G. 2015. Enhancing Student Engagement Using the Flipped Classroom. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 47(1), pp.109–114.

Gilson, A., Safranek, C.W., Huang, T., Socrates, V., Chi, L., Taylor, R.A. and Chartash, D. 2023. How Does ChatGPT Perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination? The Implications of Large Language Models for Medical Education and Knowledge Assessment. JMIR Medical Education. 9, p.e45312.

Graham, C.R. 2013. Emerging Practice and Research in Blended Learning In: Handbook of Distance Education. Routledge.

Gündüz, A. and Akkoyunlu, B. 2019. Student views on the use of flipped learning in higher education: A pilot study. Education and Information Technologies. 24.

Hang, Y., Khan, S., Alharbi, A. and Nazir, S. 2022. Assessing English teaching linguistic and artificial intelligence for efficient learning using analytical hierarchy process and Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution. Journal of Software: Evolution and Process. 36(2).

Hargreaves, S. 2023. ‘Words are Flowing Out Like Endless Rain Into a Paper Cup’: ChatGPT & Law School Assessments. Legal Education Review. 33.

Hasal, M., Nowaková, J., Ahmed Saghair, K., Abdulla, H., Snášel, V. and Ogiela, L. 2021. Chatbots: Security, privacy, data protection, and social aspects. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience. 33(19), p.e6426.

Heitz, C., Prusakowski, M., Willis, G. and Franck, C. 2015. Does the Concept of the “Flipped Classroom” Extend to the Emergency Medicine Clinical Clerkship? Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 16(6), pp.851–855.

Huang, A.Y.Q., Lu, O.H.T. and Yang, S.J.H. 2023. Effects of artificial Intelligence–Enabled personalized recommendations on learners’ learning engagement, motivation, and outcomes in a flipped classroom. Computers & Education. 194, p.104684.

Huang, C.S.J., Yang, S., Chiang, T.H.C. and Su, A.Y.S. 2016. Effects of situated mobile learning approach on learning motivation and performance of EFL students. . 19, pp.263–276.

Huang, W., Hew, K. and Gonda, D. 2019. Designing and Evaluating Three Chatbot- Enhanced Activities for a Flipped Graduate Course. . 8, pp.813–818.

Hwang, G.-J., Yang, H. and Wang, S.-Y. 2013. A concept map-embedded educational computer game for improving students’ learning performance in natural science courses. Computers & Education. 69, pp.121–130.

Jia, C., Hew, K., Du, J. and Li, L. 2022. Towards a fully online flipped classroom model to support student learning outcomes and engagement: A 2-year design-based study. The Internet and Higher Education. 56, p.100878.

Jian, Q. 2019. Effects of digital flipped classroom teaching method integrated cooperative learning model on learning motivation and outcome. The Electronic Library. ahead-of-print.

Kim, H.-S., Kim, N. and Cha, Y. 2021. Is It Beneficial to Use AI Chatbots to Improve Learners’ Speaking Performance? The Journal of AsiaTEFL. 18, pp.161–178.

Klemm, W. 2002. Software Issues for Applying Conversation Theory For Effective Collaboration Via the Internet. Available from: http://www.cvm.tamu.edu/ wklemm/Files/ConversationTheory.pdf.

Lage, M., Platt, G. and Treglia, M. 2000. Inverting the Classroom: A Gateway to Creating an Inclusive Learning Environment. Journal of Economic Education. 31, pp.30–43.

Lai, C.-L. and Hwang, G.-J. 2016. A self-regulated flipped classroom approach to improving students’ learning performance in a mathematics course. Computers & Education. 100.

Lee, J. 2023. Flipped Learning In: O. Zawacki-Richter and I. Jung, eds. Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Education. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp.1179–1196.

Lee, J. and Choi, H. 2019. Rethinking the flipped learning pre‐class: Its influence on the success of flipped learning and related factors. British Journal of Educational Technology. 50(2), pp.934–945.

Lee, J., Lim, C. and Kim, H. 2016. Development of an instructional design model for flipped learning in higher education. Educational Technology Research and Development. 65.

Lipomi, D.J. 2020. Video for Active and Remote Learning. Trends in Chemistry. 2(6), pp.483–485.

Lo, C.K. and Hew, K. 2017. A critical review of flipped classroom challenges in K-12 education: Possible solutions and recommendations for future research. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning. 12, pp.1–22.

Lo, L.S. 2023. The CLEAR path: A framework for enhancing information literacy through prompt engineering. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 49(4), p.102720.

Love, B., Hodge, A., Grandgenett, N. and Swift, A.W. 2013. Student learning and perceptions in a flipped linear algebra course. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 45(3), pp.317–324.

Lozano-Lozano, M., Fernández-Lao, C., Cantarero-Villanueva, I., Noguerol, I., Álvarez-Salvago, F., Cruz-Fernández, M., Arroyo-Morales, M. and Galiano-Castillo, N. 2020. A Blended Learning System to Improve Motivation, Mood State, and Satisfaction in Undergraduate Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 22(5), p.17101.

Manipatruni, V.R., Nannapaneni, S., Karim, M. and Abdul, S. 2024. Synthesis of blended learning and bichronous learning in improving undergraduates’ English-speaking skills through short presentations. XLinguae. 17, pp.107–122.

Martin, F., Polly, D. and Ritzhaupt, A. 2020. Bichronous Online Learning: Blending Asynchronous and Synchronous Online Learning.

Maslow, A.H. 1981. Motivation And Personality: Motivation And Personality: Unlocking Your Inner Drive and Understanding Human Behavior by A. H. Maslow. Prabhat Prakashan.

Mattis, K.V. 2015. Flipped Classroom Versus Traditional Textbook Instruction: Assessing Accuracy and Mental Effort at Different Levels of Mathematical Complexity. Technology, Knowledge and Learning. 20(2), pp.231–248.

Mazur, E. 1997. Peer Instruction: A User’s Manual 1st edition. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson.

Milman, N. 2012. The flipped classroom strategy: What is it and how can it best be used? Distance Learning. 9, pp.85–87.

Molins-Ruano, P., Sevilla, C., Santini, S., Haya, P., Rodríguez, P. and Sacha, G. 2014. Designing videogames to improve students’ motivation. Computers in Human Behavior. 31, pp.571–579.

Parra, J. and Abdelmalak, M. 2016. Expanding Learning Opportunities for Graduate Students with HyFlex Course Design. International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design. 6, pp.19–37.

Piaget, J. 1964. Part I: Cognitive development in children: Piaget development and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 2(3), pp.176–186.

Rahman, S., Yunus, M. and Hashim, H. 2020. The Uniqueness of Flipped Learning Approach. International Journal of Education and Practice. 8, pp.394–404.

Regulation GDPR 2018. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – Legal Text. Intersoft Consulting. [Online]. Available from: https://gdpr-info.eu/.

Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 55(1), pp.68–78.

Schmidt, S.M.P. and Ralph, D.L. 2016. The Flipped Classroom: A Twist On Teaching. Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER). 9(1), pp.1–6.

Selwyn, N. 2016. Digital downsides: exploring university students’ negative engagements with digital technology. Teaching in Higher Education. 21, pp.1–16.

Sergis, S., Sampson, D. and Pelliccione, L. 2018. Investigating the impact of Flipped Classroom on students’ learning experiences: A Self-Determination Theory approach. Computers in Human Behavior.

Sowa, L. and Thorsen, D. 2015. An Assessment of Student Learning, Perceptions, and Social Capital Development in Undergraduate, Lower-division STEM Courses Employing a Flipped Classroom Pedagogy In: 2015 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition Proceedings. Seattle, Washington: ASEE Conferences, pp.26–175.

Stöhr, C., Demazière, C. and Adawi, T. 2020. The polarizing effect of the online flipped classroom. Computers & Education. 147, p.103789.

Strayer, J. 2007. The effects of the classroom flip on the learning environment: a comparison of learning activity in a traditional classroom and a flip classroom that used an intelligent tutoring system. The Ohio State University.

Su, J. and Yang, W. 2023. Unlocking the Power of ChatGPT: A Framework for Applying Generative AI in Education. ECNU Review of Education. 6, pp.1–12.

Suleiman, N. 2018. IMPLEMENTING BLENDED LEARNING AND FLIPPED LEARNING MODELS IN THE UNIVERSITY CLASSROOM: A CASE STUDY.

Taha, W., Hedstrom, L.-G., Xu, F., Duracz, A., Bartha, F., Zeng, Y., David, J. and Gunjan, G. 2016. Flipping a first course on cyber-physical systems: an experience report In:, pp.1–8.

Talbert, R. 2012. Inverted Classroom. Colleagues. 9(1).

Tileston, D.W. 2010. What Every Teacher Should Know About Student Motivation. Corwin Press.

Tlili, A., Shehata, B., Adarkwah, M.A., Bozkurt, A., Hickey, D.T., Huang, R. and Agyemang, B. 2023. What if the devil is my guardian angel: ChatGPT as a case study of using chatbots in education. Smart Learning Environments. 10(1), p.15.

UNESCO 2021. Reimagining our futures together: a new social contract for education. UNESCO.

Valério, F.A.M., Guimarães, T.G., Prates, R.O. and Candello, H. 2020. Comparing users’ perception of different chatbot interaction paradigms: a case study In: Proceedings of the 19th Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Diamantina Brazil: ACM, pp.1–10.

Vanichvasin, P. 2021. Chatbot Development as a Digital Learning Tool to Increase Students’ Research Knowledge. International Education Studies. 14(2), pp.44–53.

Viriya, C. 2022. Exploring the Impact of Synchronous, Asynchronous, and Bichronous Online Learning Modes on EFL Students’ Self- Regulated and Perceived English Language Learning. rEFLections. 29(1), pp.88–111.

Vygotsky, L.S. 1978. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes (M. Cole, V. Jolm-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, eds.). Harvard University Press.

Wang, C.H., Shannon, D.M. and Ross, M.E. 2013. Students’ characteristics, self-regulated learning, technology self-efficacy, and course outcomes in online learning. Distance Education. 34(3), pp.302–323.

Wang, F.H. 2017. An exploration of online behaviour engagement and achievement in flipped classroom supported by learning management system. Computers & Education. 114.

Winkler, R. and Söllner, M. 2018. Unleashing the Potential of Chatbots in Education: A State-Of-The-Art Analysis. Academy of Management Proceedings. 2018, p.15903.

Wollny, S., Schneider, J., Di Mitri, D., Weidlich, J., Rittberger, M. and Drachsler, H. 2021. Are We There Yet? - A Systematic Literature Review on Chatbots in Education. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence. 4, p.654924.

Yılmaz, R. 2017. Exploring the Role of E-Learning Readiness on Student Satisfaction and Motivation in Flipped Classroom. Computers in Human Behavior. 70.

Transcription created with Descript (2024).

Let's talk about flip learning. You know, my story with flip learning is interesting. For, for 19 years, I taught in the traditional way. I stood up and I yacked at my students. Yack, yack, yack, yack, yack, yack. Then I sent them home to do hard stuff and I was somewhat successful. I won some awards that way.

But if you think about it, You're probably all familiar with Bloom's Taxonomy, but on Bloom's Taxonomy, this is what I was doing. I was spending the vast bulk of my class time doing the lower levels of Bloom's Taxonomy when I was in class with my students, right? The remembering and understanding stuff, I was yakking at my students.

And then I sent them home to apply, analyse, evaluate, and create. Now, think about that for a moment. Does that make sense? This is the easy stuff, and this is the hard stuff. I do the easy stuff in class. I do the hard stuff at home, or my students do. So what if we flip Bloom's Taxonomy? What if instead, there was less class time devoted to the easy stuff, and the hard stuff is what we focused in on.

In fact, I think, honestly, the best picture of Bloom's Taxonomy is this picture, where it's the diamond. I think it's unrealistic to do the, the, uh, inverted pyramid. I think what you want to do is spend the bulk of your class time, usually in the middle of Bloom's Taxonomy. Now hear me carefully, I'm not saying that you don't do remembering and understanding activities, but you don't do them in class.

So some people said that flip learning is like anti lecture. Well, I'm lecturing to you right now. But I'm doing it through a video. And you can consume that ahead of time. In fact, interact. You use less class time. So you can use the bulk of your class time for this. Because it comes down to their, really, flip learning comes down to one simple question.

This.

What's the best use of your face to face class time? My guess, it's not you yakking at your students. It's something else. So it depends on what you teach. If you're a language teacher, maybe it's practicing speaking the language. With you present. Create a scenario where you can go to the dentist office, or you go to the mall and you're having an interaction, or whatever, and then use your, your pre learning, so the pre learning activities, the stuff at the lower levels of Bloom's Taxonomy, remember that again, that's the stuff that you want to do in the pre learning activity.

Pre learning, by the way, could either be a video or text, all right? In the flipped learning world, we talk about two different spaces. Now, hear me carefully. There is what we call the independent space and the group space. The independent space is where the students are going to work alone. And here, you want to do lower blooms. The group space is when you're face to face in your classroom. By the way, face to face could be face to face in a zoom room, right? If you're teaching in the pandemic or post pandemic or online or whatever it might be. And here you want to focus on higher blooms. It's a really simple idea guys.

Do the easy stuff alone through some kind of interactive online tool. Then, do the group space higher Bloom stuff. That could be a debate. A science teacher, that's an experiment. Um, a history teacher, it's, it's maybe a Socratic seminar. In a writing class, or a literature class, it might be an overall group discussion about the protagonist in the story. In a dance class, it's actually dancing. I think maybe they learn the moves, the dancing moves. Um, they watch that in the independent space, but they actually come and practice it in the group space. There's actually sports teams who've adopted flipped learning where independent space is like learning the plays in a, like an American football league or something like that, and then they spend the group space practicing doing those things.

It really comes down to this very simple question. What's the best use of your face to face class time? And I'm going to argue it's not you standing up and yacking at your students to the whole group. You know, for me, so I'm, I'm, I'm still a teacher. I teach full time. I'm a high school science teacher. And I haven't lectured since 2007 to the whole group. And I still lecture, like, like I'm doing right now, through these cheesy videos that you're watching. This is a short, brief introduction to flipped learning and how it works.

The 7C's Learning Design Framework comprises four main phases. Firstly, in the Vision phase, educators initiate the design process by conceptualising their instructional approach. Next, in the Activities phase, they create content, decide on communication methods, collaborate with others, and consider tools for reflection and assessment. Then, in the Synthesis phase, they combine and refine their ideas. Finally, in the Implementation phase, they consolidate plans and prepare for execution (Conole, 2015).

The origins of FL can be traced back to the late 1990s. Eric Mazur, a professor at Harvard University, introduced pre-class reading materials to students enrolled in undergraduate physics courses. These materials were then discussed in class amongst peers under the supervision of instructors, which he termed peer instruction (Mazur, 1997). Mazur found that this method of instruction nurtured a deeper comprehension of course content compared to traditional direct instruction methods. Following Mazur's work, Wesley Baker coined the term 'flipped class' when he uploaded lectures and facilitated forum discussions for his graphic design course, noting a pedagogical shift from the traditional 'sage on the stage' to a 'guide on the side' (Baker, 2000). Simultaneously, Lage et al. (2000) proposed the concept of the inverted classroom, which advocated for a more individualised approach to teaching. Despite these early developments, research on the effectiveness and implementation of flipped learning remained limited (Crouch & Mazur, 2001; Strayer, 2007).

A significant advancement in FL methodology occurred in 2007, led by high school chemistry educators John Bergmann and Aaron Sams. They began recording lectures for students who missed class and eventually assigned homework based on these recordings. They observed that this approach encouraged greater student engagement and problem-solving during class time, leading to the development of their FL model (Bergmann & Sams, 2012; 2014). Moreover, their efforts culminated in the establishment of the Flipped Learning Network in 2012, which aimed to provide educators with instructional strategies and resources (Flipped Learning Network, 2024). Since then, interest in FL has grown, with renowned institutions such as Harvard and Stanford spearheading the global FL movement and advocating for best practice standards worldwide (Flipped Learning 3.0 Global Standards Summit, 2018).

1. Introduction

This Privacy Policy sets out how The Learning Lighthouse ("we", "us", "our") manages the personal data of visitors and customers in compliance with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018. Our website, www.whiskerspawsandplates.com, is committed to ensuring that your privacy is protected.

2. Personal Information Collected

In accordance with Articles 5 and 6 of the UK GDPR, we collect personal data when you interact with our site through registration, purchases, or communication. This may include:

Name and job title

Contact information, including email address

Demographic information such as postcode, preferences, and interests

Other relevant information for customer surveys and offers

3. Use of Personal Data

We process personal data under the lawful bases outlined in Article 6 of the UK GDPR: consent, contract, legal obligation, vital interests, public task, or legitimate interests. Uses include:

Personalising your experience

Improving our services

Completing transactions

Conducting analytics and market research

4. Data Sharing and Disclosure

We ensure the confidentiality of personal data and will not disclose it to third parties unless required by law or necessary for our services, aligning with UK GDPR requirements (UK GDPR, Article 6). Trusted third parties may assist in website operation, requiring them to comply with our privacy standards.

5. Data Security

In compliance with Article 32 of the UK GDPR, we employ appropriate security measures to prevent unauthorized access or disclosure of collected data, ensuring data accuracy and efficient management.

6. Data Retention

We retain personal data only for as long as necessary, in line with Article 5(1)(e) of the UK GDPR, and for the purposes specified in this policy.

7. Your Rights

Under the UK GDPR, you possess rights over your data, including access, rectification, erasure, and restriction of processing (UK GDPR, Articles 15-18).

8. International Data Transfers

We do not transfer personal data outside the UK or EEA, ensuring all data processing adheres to UK GDPR standards.

9. Changes to the Privacy Policy

This policy is periodically reviewed and updated in accordance with changes in legal requirements and best practices. Amendments will be posted on this page and, where appropriate, notified to you by email.

10. Contact Information

Questions regarding this policy should be emailed to info@markeg.com

1. Introduction

We use cookies in compliance with the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECR) to enhance user experience and analyse site traffic.

2. Types of Cookies Used

We deploy the following cookies:

Strictly Necessary Cookies: Essential for website operation.

Performance Cookies: Collect anonymous data on site usage.

Functionality Cookies: Remember user choices.

Targeting Cookies: Advertise based on user interaction.

3. Purpose of Cookies

Cookies improve website functionality and user experience by enabling personal settings and providing insights into user behaviour, in compliance with PECR.

4. Managing Cookies

You can manage cookie preferences through your browser settings, though this may affect how the website functions.

5. Changes to the Cookie Policy

Updates to this policy will reflect changes in law or best practices, with revisions accessible on our site.

6. Contact Information

For more details on our use of cookies, please contact us at info@markeg.com.

1. Introduction

Welcome to The Learning Lighthouse. These Terms and Conditions govern your use of our website and services. By accessing our website, you agree to these Terms and Conditions in full. If you disagree with any part of these terms, you must not use our website.

2. Privacy and Personal Data

We are committed to protecting and respecting your privacy. Our Privacy Policy aligns with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018, which complements the GDPR in the UK. These laws are designed to ensure that personal data is processed lawfully, fairly, and transparently, without adversely affecting your rights. For further reading see Voigt and Bussche (2017) and Carey (2018).

3. User Responsibilities

You must be at least 18 years old to use our site, or have legal parental or guardian consent.

You must provide accurate and current registration information.

You agree not to use our site for any unlawful purpose.

You agree not to breach the security of the site or access data not intended for you.

4. Intellectual Property Rights

The content on our website is owned by us or our licensors and is protected by copyright and other intellectual property laws. You may not use the content from our site in a way that constitutes a breach of these laws.

5. Limitation of Liability

Our website and its content are provided "as is." We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of the information published on our website. We will not be liable for any consequential, indirect, or special loss or damage.

6. Governing Law and Jurisdiction

These terms and conditions will be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of England and Wales, and any disputes relating to these terms and conditions will be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of England and Wales.

7. Amendments

We may update these terms from time to time. The updated version will be effective as soon as it is accessible. You are responsible for reviewing these terms periodically.

8. Your Rights Under GDPR

Right to access: You can request a copy of the personal data we hold about you.

Right to rectification: You can request that we correct any information you believe is inaccurate.

Right to erasure: You can request that we erase your personal data, under certain conditions.

Right to restrict processing: You can request that we restrict the processing of your personal data, under certain conditions.

Right to object to processing: You can object to our processing of your personal data, under certain conditions.

Right to data portability: You can request that we transfer the data we have collected to another organization, or directly to you, under certain conditions.

9. Contact Us

For any questions or concerns regarding these terms or your personal data, please contact us at info@markeg.com.

References:

Voigt, P., & Bussche, A. V. (2017). The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Springer International Publishing.

Carey, P. (2018). Data Protection: A Practical Guide to UK and EU Law. Oxford University Press.

Blended learning can take on various formats, with educators choosing the most suitable for their needs (Suleiman, 2018). According to Graham (2013), universities and colleges design blended learning models tailored to their specific requirements.

Blended learning is described as a combination of traditional information transmission, research, problem-solving, and interactive peer work (Bullmaster-Day, 2011). However, these components do not necessarily follow the FL approach, where activities occur at different times.

A study by the University of Jordan (Suleiman, 2018) concluded that blended learning with FL fosters greater analytical and critical thinking skills than traditional classroom teaching, increases interactivity, and promotes student-centred learning. Integrating technology was easier with the use of FL rather than during classroom time.

Bichronous learning combines synchronous and asynchronous activities, combining interactive peer and teacher sessions along with self-paced learning (Viriya, 2022). According to Martin et al. (2020) bichronous learning can enhance the student experience by allowing a self-paced progression through asynchronous components, while maintaining engagement via synchronous classes. Bichronous learning may also follow the FL format, with face-to-face classroom learning replaced by synchronous virtual classes (Lee, 2023).

Hyflex (hybrid/flexible) learning, proposed by Parra & Abdelmalak (2016), allows learners to choose their mode of participation: online or offline, asynchronous or synchronous. This model may incorporate FL, but the design challenges are significant with motivation being a crucial factor influencing success.

The effectiveness of fully online FL compared to traditional FL has been debated. Stöhr et al. (2020) and Jia et al. (2022) maintain that they found no statistically significant difference in average academic performance between the two. The study showed that there was a larger performance spread in fully online FL, indicating that while some students excel, others can struggle (Stöhr et al. 2020).

Online learning needs dedication and self-regulation (Barnard-Brak et al.; 2009; Viriya 2022; Wang et al., 2013). Integrating technology through FL and blended learning enhances creativity and makes learning more enjoyable, thereby increasing motivation to learn (Ahmadi & Reza, 2018; Venkata et al., 2024). Competence, motivation, mood, and satisfaction can be improved using online FL when compared to traditional teaching (Lozano-Lozano et al., 2020). An alternative view is presented by Lee (2023) who expressed concerns with bichronous, hyflex and blended learning when combined with FL, stating that a lack of motivation is the biggest challenge for success.

The creation of a policy for FL is not widely documented. However, it has been suggested it is needed to mitigate the risk of cheating by using GAI to complete pre-work and assessments out of class (Millman, 2012; Abeysekera & Dawson, 2015). Pursuing the effectiveness of such a policy may be challenging. According to Abeysekera and Dawson (2015), there are expectations of 10 to 12 hours of out of class work per subject per week within higher education policy. Yet, when students were surveyed on how much time they spend on their studies, the results were much lower. In Australia, it was found that this was around 10 hours per week in total across multiple subjects (Coates, 2010). This raises the question whether motivation is a more important factor to consider for compliance to completing work as opposed to a policy for out of class FL work.

Although the usefulness and engaging qualities of GAI have been discussed in this paper, the use of these tools have the potential for misuse and over-reliance (Bernacki et al., 2020; Fullan et al., 2023). Fullan et al. (2023) described how there is a lack of GAI policy in education, which is relevant in a FL context. UNESCO (2021) identified that human work should be at the centre of education. Yet, in a flipped learning environment, there is a risk that students may rely on AI to understand and generate the work they should be doing themselves (Fullan et al., 2023). Hargreaves (2023) and Chan (2023) noticed that concerns have been raised about the significant risk of academic dishonesty within higher education. A study found that 75% of students believe using GAI for cheating is wrong but still do it, and nearly 30% believe their professors are unaware of their use of the tool (Chan, 2023). Should formative and summative assessments be part of post-work in flipped learning, clear policies must be in place to counter these risks. Chan (2023) observed that this development has prompted demands for more stringent regulations and harsher penalties regarding academic misconduct associated with AI. Chan also explained that there is an urgent need to develop an AI policy in education that prepares students to work with and understand the principles of this technology, which is important in an FL setting where students are expected to research and complete individual work.